The Language of Dreams

From the anthology Becoming American. Edited by Meri Nana-Ama Danquah. Published by Hyperion, 2000

I .

To speak Chinese is to inherit the memory of hunger. On lunar New Year's eve, flushed with wine and beef from the fire pot, Baba's eyes grow misty. I know what my father is going to say. On a cozy, full belly, he is reminded of the past on a empty belly. "Ahhh, there was that year when the locust swarmed across the provinces, eating up all the corn, the rice, the millet. What could the country folk do but cook locusts for their dinner," he would say. Or, "I remember toward the end of the Japanese occupation, all we had was soybeans. We were ravenous, but we knew not to eat too much of it all at once, because the stuff swelled in the stomach and could kill us."

I am a great believer in ming, the Chinese for life, but also fate. Had I been born on the Mainland of China in 1960 instead of the island of Taiwan, I may have been one of the over thirty million Chinese to perish in the worst famine known to mankind.

To be born in China in the twentieth century is to live life as a colossal waste: wasted plans, wasted opportunities, wasted resources. Even men and women of talent born into privilege have disappeared without a murmur in the maelstrom. To understand Chinese means to hear the underlying layers of cynicism born of an ancient country of interminable wars, of a people who have had to contend for too little, too long. Take the adage: One thirsty monk will carry two buckets of water on a shoulder pole; two thirsty monks will carry one bucket of water on a shoulder pole between them; three thirsty monks will remain thirsty because each thinks the other two should go get the water.

I felt I was tainted simply because I was keen to the nuances of cynicism. I felt evil. It didn't matter that I was not a misanthrope, but as long as I understood what was being said, I could not escape the legacies of a culture whose optimism, and perhaps, life, was ebbing. If only I could be immune to cynicism, I would truly become American--innocent, open, sunny.

I have often envied my American-born Chinese friends who are seemingly cleanly severed at birth from the Chinese language. They learned their first words in American English, and their souls tend to brightness and laughter. When they visit China, they are oblivious to the darkness which swirls about their ears; they are protected by their ignorance. I, on the other hand, began soaking up Chinese inside my mother's belly and did not become immersed in English until I came to the United Sates in 1967. When I am in China, I feel every slight, slur and nastiness on the crowded Beijing streets as deeply as flesh wounds.

Chinese is the language of memories as thick and pungent as fermented bean curd. Old, stale, fulsome. What did I want with memories? When I pad past my parents' bedroom late at night, their heads have rolled together where their pillows meet, nose to nose, they reminisce, sotto voiced. Or if a duet of sustained breathing emerges from their open door, I know they are dreaming, in Chinese, of course.

Baba, as all obstinate souls do, dreams about the past. The Daoist uncle who rolled his cigarettes with the pages of his books after reading; the Patriarch, Baba's grandfather, who loved chrysanthemums and boasted over one hundred varieties in his garden; his mother, bent over the lamp, sewing cloth shoes for him while outside, the withered grape leaves clatter on the vine. The souls lost in the chaos of time and war, flit across Baba's brow like shadow puppets.

He dreams of the treats from his childhood, the sesame encrusted hamatumi, toad-spitting-honey--jam-filled cakes sold on I the streets--or frozen persimmons, heavy with sweetness, spooned and eaten like ice cream. Baba's statement on his first day in America: "I'd rather die if I have only this foreigners' bread and milk for the rest of my life."

Chinese is more than an ethnic identity; it is also a system of belief, with its dogma, prejudice, and guilt-inducing credo. "What? You're not marrying a Chinese? What? You say you're going to become an American? You will always be Chinese no matter what citizenship you take up. China will always have a claim on you." In China there are Buddhists, Daoists, Muslims, Confucians, Christians among a host of religions, but each person, above all, is born spiritually, piously, religiously Chinese. There is no getting away from it.

II

This house sitting on the sunny slope of Carmel Hill which faces the coastal Santa Lucia range is filled with my parents' blue and white porcelains, cloisonné's, antique screens carved with scenes from The Romance of the Three Kingdoms, a Chinese classic of intrigue and war. This is the house whose language, iconography, beliefs and values I had raged against as a young woman. I wanted to run away from the Chinese universe I had been born into and launch into an American world view, free of the weight of memories, only to return at the age of twenty-six, seeking refuge in all that I had once rejected.

It was all in the cliché of love gone wrong, turned violent. Lover turned stalker.

My prince charming was older by a mere six years, but to me, a student of twenty, he had all the answers. He was a rock climber, a musician, a builder. He was big, brash and blond, and never apologetic. He was not the diminutive, myopic Chinese boys with fine, white hands I had known.

Slowly, almost imperceptibly, but with eyes wide open, I had relinquished my autonomy, my responsibility for my own destiny to a man who I believed would be my guide and protector. I had relinquished power to someone willing, capable and happy to manipulate me for his own purposes. Manipulation is an artful blend of abuse and sweetness; without the sweetness, who would be so blind as not to recognize abuse in all its nakedness. In time as I "grew up," as my own ideas and inclinations reared and abraded against his, he did not hesitate to apply his fists to my body so as to wrench my mind his way. I will always remember the look of intense fascination on his face--a look almost of joy--as he studied the black bruise he had left on my upper arm: it was in the perfect shape of his hand. I did not learn what freedom was until after I learned all about slavery.

I had awakened from my drunkenness about love to a half- articulated remembering that I must return to origin to be safe again. I came back to my father and mother's house, this Chinese house."

"Look what trouble you've brought on yourself. Your life is a disaster!" my father said. He did not let me off easy. The Chinese believe your body, your life is a gift from your parents. You must treasure this gift. I had only made a mess of the life I had been given.

My bodily soul wanted comforting, but severity was what I truly needed: a stern teacher who demanded spiritual clarity, someone who would not give solace, but make me afraid of who I had been. My father was the stern teacher.

This has always been a house of heavy expectations, of demands of excellence, where mediocrity is taboo, because to be mediocre is to know the taste of hunger, to perish. My parents had to be talented, excellent, sublime, fleet, strong to make their way out of the landscape of war and struggle to this American shore. If they were not these qualities, at least they knew to unfold their own myth: they had to believe that they were not just lucky, but luck itself.

But the irony is that in achieving America, which rendered them safe, they became insignificant. On arrival, they lost their language, the language in which they first learned to dream. They had come to America with nothing except pockets full of stories, but they had lost their voices. In Chinese, they were bards and minstrels; in English, their Chinese-hardened tongues were less than song-like.

I was confined to the house for my safety. If I managed to go out briefly, accompanied by my mother, Baba waited with palpitating heart, jumped at the sound of sirens. He was justified in his fears: my stalker had sent a hail of bullets through the office window of the lawyer who took my part, and later, ransacked our home, taking photographs, mementos, volumes of my father's poems written in his own calligraphy.

The violence that followed me home only served to confirm my father's favorite mantra: "It is dangerous. The world is dangerous." War and the torturous path of escape had taught him this and now he found confirmation even in his time of peace.

How will you possibly manage to protect yourself? friends, the police, the court, the lawyers asked me. In the deepening crisis, it was China that offered me a haven. A place where I could disappear in the crowd of over one billion and find safety, live productively.

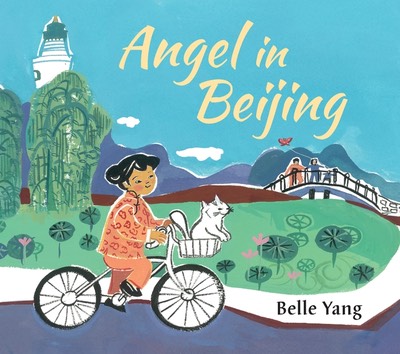

In the fall of 1986, at the age of twenty-six, I flew to Beijing to study classical Chinese art, focusing on the great tradition of landscape painting--an art of time as well as space. I learned to cast away Western perspective and vault into the sky like the Monkey King of legend--to see the world from multiple angles (the Chinese landscape is intensely different from a Western one, where the viewer remains, still as a rock, at one fixed point).

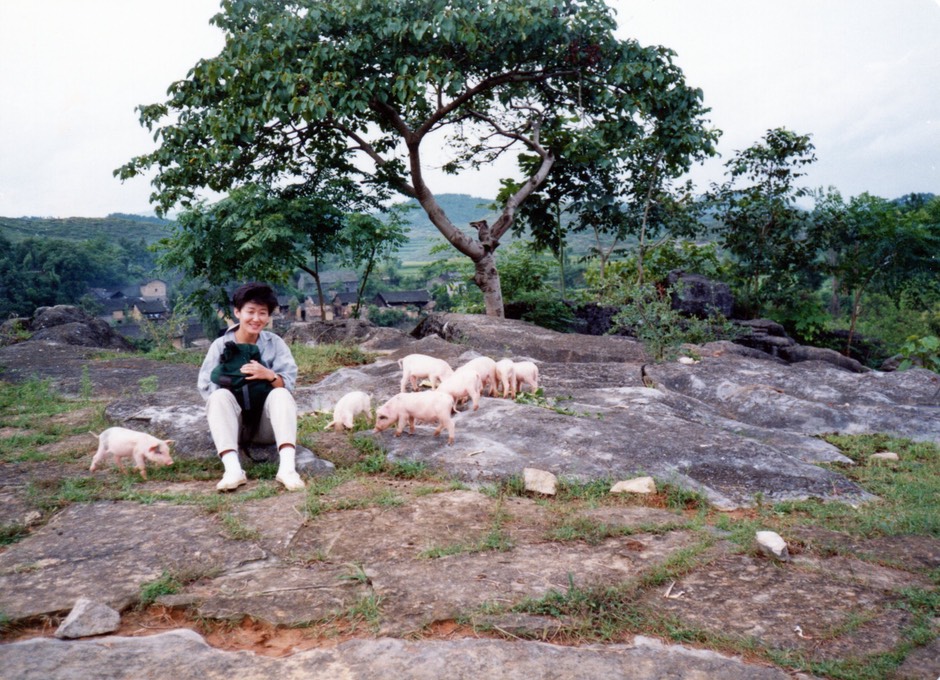

During my three years of study, I roamed across the land, sketching, painting, looking. I reached regions closed to foreigners, to which my yellow skin gained me easy entry. I traveled the Gobi Desert along the Silk Road, where Buddhism first made its appearance in the Middle Kingdom; I dug into the yellow earth of the Great Northwest and laid my hands upon pottery, art of the late Stone Age, fitting my fingers into the clay imprints of hands left by craftsmen of some seven thousand years ago; I returned to the frozen Manchurian north to celebrate Spring Festival, the Chinese New Year, with my grandparents, whose heads were frosted white with layers of remembrance; I submerged myself in the Hunan countryside of the Miao tribes, where the only foreigners seen previously were travelers from a neighboring county.

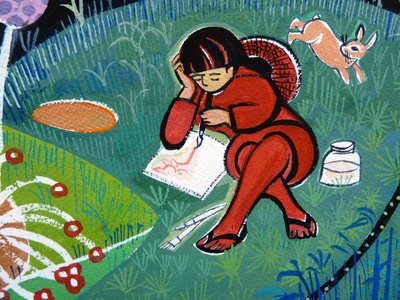

In my wanderings across a land of vastly different temperaments, my eyes were opened to a wealth of folk art, the cultural antithesis of the lofty, scholarly classical Chinese painting I had come to study. My heart was moved by the paper cuts, the vibrant graphics of the New Year prints, the naïf paintings of the peasants, each region stylistically distinct. These were works of men and women deeply rooted in their soil; works populated with farm animals, fruits of the field and stream; they were celebrations of birth, marriage, harvest, the seasons, Heaven and Earth, youth, old age, and death. The art of the country folk swelled with candor and humor; in their very artlessness they captured life more directly than any attempt at careful imitation could ever do.

It was in the countryside where I was able to dispel for myself the myth that Chinese and cynicism went hand in hand. On a painting excursion to Hunan, I was invited inside a thatched farm house whose front doors were thrown wide open, never locked. Two old farmers offered me a bamboo fan to cool off with, and water to slake my thirst. The brothers all the while smoked their pipes and smiled their gap-toothed smiles at me like children. They did not ask this stranger where she was from or why she was pestering around their village. They simply provided me with what they themselves would have wished for on a hot summer afternoon.

In the spring of my third year in China, the energy I had sensed on arrival, an underlying tension, a raw nervousness, a fluttering excitement, stirring below the surface of the society emerged and manifested itself in heady days of hope and optimism. New ideas had brought vigor--most pronounced in the cities; fresh ideas were surging from across the seas; suppressed ideas welled up from below ground. I felt as if every day I would awaken to epochal changes. The faces that greeted me on the streets of Beijing were open and candid as I had never seen before. Graciousness reigned; gone were the sharp elbows and knees of the anonymous crowd. The leaden dullness of slouching spirits was gone; eyes sparkled. Workers stuffed their entire month's salary into donation boxes to support the struggle of the students on hunger strike in Tiananmen Square. And I was as excited as anyone.

As time progressed, the energy grew wilder, the voices of the people grew louder, culminating in the passions of "Democracy Spring." But I saw it quelled. Brutally. And in the aftermath of June 4, 1989, I saw books burned, stories destroyed. I saw artists and writers numbed into silence. Great cultures tell life-sustaining stories, but in China, small lies choked the air.

The abuse I witnessed was parallel to my own personal narrative but on a grand scale; I understood the stupid thought- control, the purposeful thought-manipulation, the insidious violence--deeply, acutely. The mechanism of fear, whether applied to one human being by another or by a government on its people is one and the same.

To swallow your voice, to keep stories buried deeply beneath layers and layers of silence is to live in a state of bondage. Stories are magic. Stories make us individuals. They make us free. They have power to make trouble for rulers, for a story is world upon itself: it has its own logic and cannot be ruled at all. That is why when a new emperor comes to the throne, books are burned and fresh versions of history are written to his liking, are published.

Physically depleted, in spiritual exhaustion, I returned to America late in 1989, but I returned with gratitude in my heart for the freedom of expression given me in America. I returned convinced that I would firmly grasp that generous gift with both hands.

III

In this Chinese house of my parents, I found peace, five layers deep. I continued to be confined to the house even after my three year sojourn, for the man who wished to do me harm was still a reality of my landscape. I was forced to leave the streaming crowd that seems to know its direction. I had no clear direction and initially felt bewilderment.

My mother and father stood guard as my Door Gods, the Generals Hen and Har with their bows and arrows, protecting me from evil spirits.

Keep your mind, eyes and heart quiet, they said. Do your calligraphy as an exercise in meditation and by the end of the year, you will know precisely what you must do. You won't have to step out; opportunities will present themselves to you at your very door.

Yah, right. What opportunities? I did not believe my parents' words, but they proved to be prophetic.

The book project grew organically, a marvelous living thing; it sprouted, developed long shoots, branched, formed thick fat leaves, flowered and bore fruit.

The stories first came as a trickle. As my mother cooked over the stove, she told me about my grandmother and how she would save the umbilical cords of her babies, wrapped in crimson paper. I was inspired to paint and write a vignette. My father, not one to be left out, got into the act, too, and began to tell stories of Manchuria in the season when the sorghum was ripe, tales of men and women who colored his childhood.

The material for the first chapter of my book, Baba, began on a dark and stormy night, no less. The power was out and it was so cold, the three of us simply crawled under the covers of my parents big bed to wait out the storm.

I've got a ghost story for you, Baba said and told a tale of widowed Grandmother Sun who lost her only child to the wolves that lived in the willows along the sandy banks of the river Liu. Grandmother Sun was often seen among the tall, ripening sorghum, parting the tassels of the plants. "stop this tomfoolery. Quit your fighting," she would say.

When the power came on, I sat up in my own bed and scribbled down what Baba had told me. The next day I asked for more stories and he provided. They were snatches of his awakened memories--not enough detail to even consider an entire story, let alone a book--but they were so vivid and flavorful, textured, poetic, heartrending. I pressed Baba for more details.

My father and I had no natural understanding. He read Zhuangzi, the Dao De Jinq. the Confucian teachings, and tomes compiled by historians dynasties ago. His spiritual address was in China, and mine so much in the West. For Baba, retrospection and nostalgia dominated; the present and the uncertain future was filtered through the vast experience of a Chinese diaspora.

China prepared me to enter into the landscape of my father's childhood to understand the values that shaped him. I was able to tap into the original language, not only the spoken language, but the symbols, the iconography, in which his spirit was nourished, his ideas were given form. Only because I had embraced the Chinese language could I ask questions of depth that would stir him enough to carry me into the past. We are shaped by the language we first learned to dream in.

There is a particular sensitivity and emotional experience reached through Chinese--our peculiar written characters composed of word-pictures and the direct, haiku-like phrase structure. Chinese is first and foremost poetry. It is this language--poetry that makes us think or feel or dream the way we do. The Chinese language is art in that in its written form, it retains its pictorial identity. Art is important in influencing our mental make-up as diet over our physical makeup.

Through Baba's stories, I learned to see the child in him, the wonder in him, where once I had seen the cynicism of a tired old man who warned me incessantly about the dangers of the world. In recreating his past through words and pictures, I made friends with the boy of eight who ran barefooted in the sandy soil, stealing watermelons on a hot Manchurian summer afternoon.

Most of Baba's tales were about my ancestors. In the long days that stretched into long years of work at my writing desk, I felt the spirit of the ancients hovering over my shoulders, guiding me, protecting me. I felt a responsibility to rescue them from the deep well of forgetting. As the past took shape with great vividness, I came to understand the chain of events that nourishes the present like an umbilical cord. Knowing the past means knowing who I am today and the possibilities for unfolding the future.

At first my father did not trust me with his stories. When he read the drafts, he was hardly stingy with his criticisms if he deemed I had the texture of the landscape wrong or history wrong. Sometimes an argument would be sparked by his nasal tone of voice or my brusk retort and Baba and I would not speak to each other for days. The Chinese say you must fight with a man to know a man, and in the long years of close collaboration, he and I certainly got to know one another well, and in time, we learned to fight productively, the tension from the arguments dissipating in a matter of hours.

In the time of private concentration, I did not step outside except to take long, luxurious walks with my parents. The three of us would go out through the back fence into Hatton Canyon, our private sanctuary, for our daily communion. During our stroll, Baba would often elaborate on the stories he had told or share a song from childhood. When it rained, we put on our galoshes and looked for water skaters in the puddles. Sometimes we returned home with pine or cypress seedlings that we found sprouting among the blackberry brambles. The heavier saplings Baba carried with pride on his shoulder as if he'd bagged a wild boar. My parents replanted them for me. just outside our fenced yard. They would not likely see the trees grow to full maturity, but they were thinking of the long years ahead of me when I would enjoy myself as mistress of the house in the forest.

On some evenings, when I had completed a chapter, I would read it out loud while my parents listened, Mama's eyes closed in great concentration. The three of us would grow excited by the strange beauty, humor and humanity of the forgotten stories, or weep for the injustices of a world at war. Baba's memories would come alive and more details were extracted from the bottom-most layer of his forgetting. "Ohhh, this is too good. The world is going to love it," Mama would say, stamping her feet like a child.

I have come to believe that the Chinese food culture has been preparing me all my life to work closely with my parents. Sharing, self-restraint, respect for elders and care for the young began at the tips of our chopsticks. In this house, where we politely slurp noodles in unison, the preferred eating utensil is the bamboo chopsticks, not the knives and forks which the Chinese consider weapons of war. Our food is bite-size, sharing from common main dishes instead of sawing away at individual slabs of meat on individual plates. With the opposite, unused ends of her chopsticks, Mama will pick up a piece of tender snow pea and deliver it into my bowl, or Baba will place the last prawn atop of Mama's rice which she will decline with a "ni chi ba," you take it." There is no "crossing the river" allowed, which means to stretch our arms across the table over dishes in front and reaching for desired morsels in a far away dish. We eat what is in front of us and take what our chopsticks first touch. By eating at an affable pace, it is the responsibility of those at the table to make sure that everyone has had a fair share. As a child, I was scolded for digging for green peas from the main dish and popping them into my mouth, one after another without pause, or for leaving kernels of rice in my bowl. "It's by the sweat of the farmers' brows that you're provided this rice. Do not waste it. If you do, you'll grow up and marry a man with pockmarks," my mother would say, a threat Chinese mothers have been repeating for at least five thousand years.

IV

I was certain my writing would find its way out into the world. I felt that once I had put down the last period in my manuscript, my work was fully complete and had a life of its own. It was real. Publication would be joy, but the writing itself was red-blooded life. It was lucky I was ignorant of the hurdles to publication. Had I known of all the reasons why my work would not find an audience, I would have been too frightened to begin. As it was, ignorance was bliss. I had a beginner's mind. To the beginner, every thing is possible; the expert knows too well the limitations.

With the 1994 publication of Baba: A Return to China Upon My Father's Shoulders, my father was finally able to shake off the paranoid feelings of danger that had dominated his life. In lending him my voice, I had made him real, an individual, someone who could not be snuffed out under boots of adversity. I had rendered him safe. I was Hua Mulan, the woman warrior of legends, who cut off her tresses and went into battle in her father's stead. It was now my father who was traveling America upon my shoulders.

Baba, at the age of seventy, looks younger today than he did in his fifties. The frown-creases have been smoothed over. The cynicism, the cold snap in his eyes is no more. Readers, young and old alike, call him Baba when they have a chance to meet him. He likes that.

In the process of writing our family tales, and the stories of the overlooked, those who have disappeared in chaos of the Chinese maelstrom without a complaint, I had written fear out of my own life. In carrying the stories out into the world, I discovered the strength of my own voice. I, too, had made myself real, an individual. Free. Some time after the publication of my second book, The Odyssey of a Manchurian, I awoke one morning and felt absolutely no fear, only my soul somersaulting. The feeling was a surprise. I shouted praise: Thank you, Heaven Above, for providing me with an enemy, without whom I would never have learned about patience. He stripped me down to the essentials, reduced me to the purity of origin so I can be the kind of human being I was meant to be.

V

What language do I dream in? They say when a person is close to dying, she is left with the ability to speak only her first tongue. I suspect I will die in this house telling bad jokes in Chinese. Some caregiver, dusting the myriad antiques my parents collected over the decades, will say of me, "Oh, she loved to somersault in the grass, and she was protective of her solitude--wrote and painted almost every day. She came to America when she was seven years-old, but she said she did not truly become American until she took up her past and began telling stories of old China."