In March of 1991, a friend of mine in San Francisco, Sue Yung Li, sent me a package with a scribbled note: "Thought you might enjoy reading this." Inside, she said, were photographed illustrations painted by a writer-artist named Belle Yang. Also included: a dozen pages of Belle's prose--something to read in my spare time.

I found myself in a guilt-inducing predicament, for there I was, involuntarily holding in my hands another writer's passion and dreams, a life's work that was either about to blossom or wither, depending on luck, the presence of angels, and the kindness of strangers.

Unfortunately, my reserves of kindness had long been depleted; I didn't have time to write my own work, let alone extra time to read that of a stranger. With much guilt weighing on my heart, I sadly placed the young writer's unopened packet in the pile destined for The Junkmail Graveyard, otherwise known as my recycling bin.

Though I lacked kindness, I have had no lack of angels in my life. I cannot explain or describe who these angels are, only that they have showered me with a considerable amount of kindness and luck. Also, they ceaselessly remind me of this fact, which causes me to suspect they are mostly Chinese. In any case, my angels believed that I'd soon come to my senses and open Belle Yang's packet. Didn't I remember, they asked, that they had helped me in just such a way when I was an unpublished writer not so long ago? Didn't they help guide my early writing into the caring hands of writers like Amy Hempel and Molly Giles, while others might have turned my early efforts into handy strips of firestarter? In due time, the angels assured me, I'd retrieve Belle Yang's packet from the graveyard pile. I just needed to be nudged. Ever so lightly.

Over the next few days, Belle Yang's packet fell out whenever I reshuffled the pile. It surfaced to the top, no matter how many times it was buried beneath multiple copies of Victoria's Secret catalogs and sweepstakes notices. There were other hints. A cousin named Yang called.

An issue of Belle Lettres arrived and I developed an insatiable desire to hear the sound of bells, not just ordinary bells, but Chinese bells. On my desk was a pair of old copper clappers I had recently found in an antique shop. I clanged them together, and they produced a spectacularly resonant trrrnnng! that floated into my chest, flowed into my heart, then stubbornly lodged into that place of memory that nags at you like a universal mother asking you if you've done your homework yet. Not yet, not yet, not yet. Trrrnnng! You know you're going to have to do it, the angels told me.

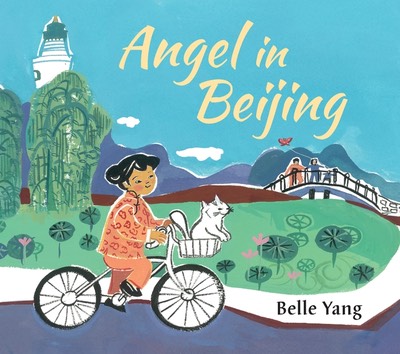

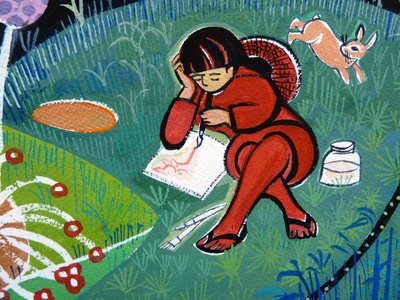

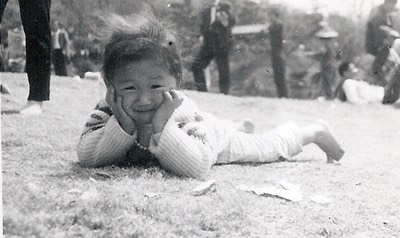

I opened Belle's packet. Glossy photographs fell out, the illustrations Sue Yung Li had mentioned. they are stunning: splashes of watercolor creating deceptively simple images woven with vibrant patterns. The paintings are very much alive, capturing balance and disharmony between this world and the underworld, between heaven and earth, between humans and nature. They are both scary and humorous, personal and, yet, a larger view of the world. Whoever this Belle Yang is, I thought to myself, she paints well, I grant her that.

I then picked up the pages and began to read the vignettes of Baba, based on stories and boyhood reminisces of Belle Yang's father. Soon I was gasping and sighing, hearing the music of Belle Yang's words, seeing and experiencing the fullness of a once-lost world she had re-created with the same vibrancy as her paintings.

In reading those few pages, I sensed the excitement veteran editors must feel when, in discovering a fresh voice, they once again find joy abundant enough to sustain them through next year's tedious editorial meetings. Belle's voice is so true and pure, it is capable of washing away the grimy layers of cynicism, the dust of ennui, the greasiness of business. I felt lucky to be that recipient of her work. I called Sue Yung Li and thanked her. I called Belle and congratulated her. I called my agent and said, "I have something very, very special I think you should see."

This is not say I discovered Belle Yang, for others had already discovered her writing and art before I did. but that was how I discovered once again why I love to read stories, why I once wanted to paint stories myself.

Baba is a work of twin arts. It reminded me of the earliest reason I became a writer: As a child, I wanted to be an artist. Using charcoal, pastels, and paints, I sought to capture my perceptions of the world or, rather, a precise and specific moment that conveyed what I saw, what I believe, what I felt was true about life that no one else could possibly understand unless I rendered it clearly and well.

I possessed more-than-average abilities in executing reasonable likenesses of still life subjects--for instance, my tabby cat, Fufu, lying on his back in the sun. Adults praised my work: "Why, that looks just like Fufu!" But I could capture none of what was more important to me. Not the differences: the intelligence of Fufu's naughtiness, for example. Nor the emotions: the twist in my heart when Fufu, lost for days, wailed to me from within a locked closet. Nor the ephemeral aspects of life's quiet intensity: how my breath on fufu caused his ears to flutter just like the moths that caressed our porchlight.

I always fell short of drawing what I felt, what I saw in that one magical second. And while there is enormous satisfaction in the physicality of drawing, there is a stone-in-the-throat sort of disappointment in seeing large and pitiful results before one's very eyes. Even though I swept my brush boldly across the page, even though I dabbed at details with blind patience, the right lines, colors, and shapes always eluded me. And so I eventually turned to my tools of second choice: I tried to use words to paint pictures.

Those are the reasons I admire and envy Belle Yang's double talents. She writes what she sees and feels. She draw what she sees and feels. She does so with mastery in both crafts. As Yang points out herself, in Chinese art there is no separation between pictures and words. They come from the same source. She creates painted stories, as well as story paintings. Through bold strokes of poetry and color, yang evokes a likeness of a world now gone but retrieved through memory: the redbeard bandits, the son on the rooftop crowing instructions to the dead, the hwwoolong sounds of bombs landing in the marsh. She captures her own family folktales and long-standing rumors, as well as our own willingness to believe they must be true: that a prophetic dream from a goddess could foretell both judicious and unfair results, that the origins of one family's wealth came from a glowing three-legged creature that served as a divining rod to buried urns of gold.

What is equally amazing to me is the fact that Belle Yang sees transparently between Chinese and English. She's an American writer who writes in English and thinks in Chinese. Her writing feels Chinese to me without the awkwardness of word-for-word transliteration and without the paleness of "something lost in translation" for the sake of accessibility to the Western reader. It is as though we, the readers of English, can now miraculously read Chinese.

As an American writer who understands Chinese but speaks it like a child, I both appreciate and envy Belle Yang's literary feats. It is one thing to write proficiently in two languages, another to sense the world in two languages. By that, I mean that Belle Yang senses the lost world of her father in Chinese: the brusque and matter-of-fact rhythms of life, the folk imagery, the historical undertones of classical art, the noisy onomatopoeia of country and city life, the sour, appeasing, and deeply satisfying tastes of food, the adverse and harmonious relationship between humans and nature, the bitter and belly-laughing ironies, and the circular ways in which everything makes perfect if not logical sense. Yet she conveys all this with English, with poetry, with the universal power of language. she has created a world we can lose ourselves in, and when we emerge we are all the better for it. For a few lingering moments, we can even see magic in our own world. What a gift.

Baba makes me want to paint again. With watercolors, with words, whatever I can use. I want to paint the angels who urged me to see Belle Yang's work.